Introduction

“Cauda equina syndrome1 is a potentially devastating spinal condition associated with substantial morbidity, and often leads to litigation.”2

Although first described nearly a century ago, the medical community continues to struggle with an agreed upon definition for Cauda Equina Syndrome (CES). More importantly for patients who suffer from its often catastrophic results, the medical community continues to struggle with timely diagnosis and treatment of CES.

This article endeavors to highlight both the current state of relevant medical literature, and the medical and legal issues that may arise in claims alleging delays and failures to diagnose/treat CES.3

What is CES?

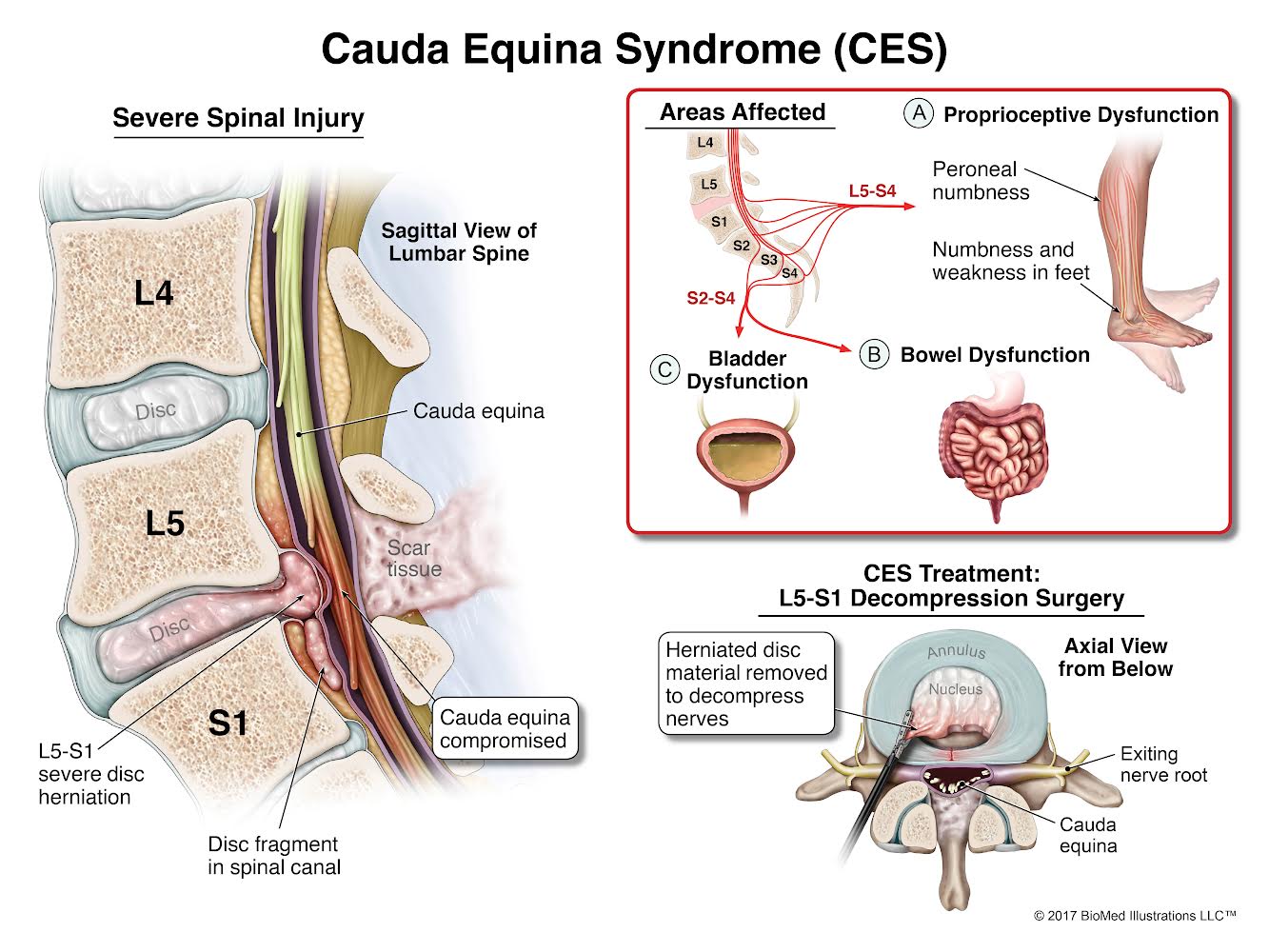

In Latin, “cauda” refers to a tail, and “equina” means horse. The spinal cord ends at the upper portion of the lumbar spine. There the individual nerve roots spread out in a form similar to a horse’s tail. Hence the name “cauda equina”. These nerve roots provide motor and sensory function to the lower limbs and pelvic organs, including the bowel and bladder. Generally, CES occurs when there is dysfunction of these nerve roots.4

Typically, the cause of this dysfunction is compression. Instead of the nerve roots floating in the space of the lower spinal canal, something pushes into the space, compressing the nerve roots. When this occurs, motor and sensory function of the lower extremities, the bladder, the bowel, sexual organs, and the perianal area can all be affected.5 “Saddle anesthesia” is a common presenting symptom – sensory dysfunction in the area of the body that would contact a saddle (the anus, inner thighs, genitals and buttock region).6 Pain can also be a presenting complaint, not only in the legs but also in the low back.7

Compression can occur in different ways, chief among them lumbar disc herniation into the lumbrosacral canal at the L4-L5 or L5-S1 level. Other disease processes causing CES include hematomas, tumors, infections, trauma (such as gunshots or falls), birth abnormalities, spinal arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), postoperative lumbar spine surgery complications, and spinal anesthesia.8

Defining CES

CES is characterized in the medical literature as rare or uncommon, but unquestionably it is a disease known to not only spine surgeons but also radiologists who may interpret imaging studies of the spine, and front-line providers such as emergency department physicians. Approximately 1% to 3% of herniated lumbar discs requiring surgery may cause CES.9 While uncommon, it is also characterized as a surgical emergency.

Currently there are four defined stages of CES:

• CES Suspected (“CES-S”) – bilateral radicular pain

• CES Incomplete (“CES-I”) – urinary difficulties of neurogenic origin (e/g/, altered urinary sensation, loss of desire to void, poor urinary stream, need to strain to urinate)

• CES Retention (“CES-R”) – Neurogenic urine retention (defined as painless urinary retention with overflow incontinence)

• CES Complete (“CES-C”) – Objective loss of cauda equina function, absent perineal sensation, patulous anus, paralyzed and insensate bladder/bowel.10

Diagnosis and Treatment

Diagnosing CES can be challenging, since patients may present with varying constellations severities, and onsets (acute or gradual) of symptoms.

The diagnosis of CES is initially made clinically with a comprehensive history from the patient and physical exam. Radiographic studies (usually MRI) are used to confirm the diagnosis and help guide treatment. Certain “red flag” symptoms include urinary retention; urinary and/or fecal incontinence; saddle anesthesia; weakness or paralysis of usually more than one nerve root; pain in the back and/or legs; and sexual dysfunction.11

Medical/Legal Issues

Because of the devastating effects CES can have on patients, and the often multiple attempts patients must make seeking help from the medical establishment, it is not surprising claims are made. Certainly, the magnitude of harm is a factor in analyzing the merit of any such claim. Leaving aside damages, claims involving CES tend to include unique issues relating to both negligence and causation.

Negligence – Potential theories of liability

Delays in diagnosis of CES are not uncommon. This can be due to negligence on the part of front-line providers such as emergency department physicians, or specialists such as radiologists or spine surgeons.

In the authors’ experience, most reputable front-line medical experts will not fault an ED provider for “missing” a diagnosis of CES on the patient’s first visit absent egregious signs and/or symptoms in the chart. Back pain alone is one of the top five most common emergency department complaints.12 Because of this, front-line providers such as ED doctors must have a “high index of suspicion” to detect CES in patients with back pain. If not, she or he may fail to robustly evaluate other possible symptoms that may exist but may not be the patient’s chief complaint.

Delays and failures to diagnose CES can result from an inadequate history being taken. For example, a clinician may fail to ask questions about a patient’s bowel, bladder, or sexual function, or sensation changes in the saddle area. If a patient has back pain and one of urinary retention, urinary incontinence, fecal retention, fecal incontinence, loss of anal sphincter tone, sexual dysfunction, or saddle anesthesia, CES should be on the doctor’s differential diagnosis and should be ruled out prior to the patient’s discharge.

Similarly, any rapidly progressing neurologic deficits is a red flag, and failing to elicit such information may be grounds for a claim. Or attributing reported urinary incontinence to a more benign cause, such as the use of narcotic pain medication, may result in missing a CES diagnosis.

It is important for any ED physician suspecting CES to ask about a recent history of trauma. One journal article noted that as many as 62% of patients eventually diagnosed with CES had a recent history trauma, including falls, car crashes, weight-lifting, and chiropractic manipulations.13

An inadequate physical exam can also result in a diagnostic “miss”. Without adequate motor and sensory testing of a patient’s bilateral lower extremities, insidious symptoms may be missed. A complaint of urinary retention, as above, may be chalked up to opioid use, when a simple and readily available bladder scan (taken before voiding and then after to measure postvoid residual volume) could lead a reasonably prudent provider to the correct diagnosis. Often providers are reticent to perform a rectal tone exam (also known as a “wink” test). Failing to perform such a test may mean the physician misses a “red flag” that would otherwise lead to diagnosis.

Communication can be vital in assessing a patient for possible CES. Because it can take multiple visits to an emergency department before the diagnosis is made, careful and accurate charting is important. Unfortunately, in this age of electronic medical records, it is not uncommon in the authors’ experience to see a series of “normals” charted when the patient herself paints a very different picture.14

An ED provider may be negligent if he or she has sufficient clinical indications to warrant imaging to confirm the diagnosis of CES but fails to order such imaging. Typically, this involves an urgent/emergent MRI. Although CT imaging is more commonly available in emergency departments, it will fail to diagnose many large disc herniations (as well as hematomas and abscesses) that MRI imaging will identify.15

Due to the need for timely diagnosis, best practice is for an MRI to be performed within one hour of clinical diagnosis of suspected CES.16 If the ED facility does not have access to an onsite MRI machine, the patient must be transferred somewhere with MRI capabilities.

Similarly, communication between providers – both within the chart from ED doctor #1 to ED doctor #2, and between different specialties – can be substandard and result in a serious delay for the patient.

One such communication error is when an ED physician fails to involve a spine specialist in working up the patient. Any “red flags” in the setting of suspected CES warrant an urgent consultation by either a neurosurgeon or orthopedic spine surgeon.17 A “curbside consult”, or unofficial consultation, is often insufficient, particularly when important clinical information is omitted.

Another communication error can be something as simple as an ED physician requesting the hospital “care coordinator” call the patient and facilitate an urgent consultation with an orthopedic surgeon, and the coordinator dropping the ball.

Communication errors can also occur surrounding the results of an MRI study. Such results may simply not be forwarded to the appropriate provider. Or, perhaps more likely, a radiologist him or herself can fail to timely communicate the need for urgent intervention.

So too, radiologists can simply “miss” the severe compression on imaging causing the patient’s symptoms.

Possible negligence defenses

Because the medical establishment itself has to date been unable to reach consensus on a definition of CES, it is no surprise that defenses to such claims highlight the lack of clear definitions and variable presentations, making diagnosis difficult in their opinion in all but the most obvious cases.18

Some highlights from CES literature illustrate the ammunition defendants have making this argument:

• “Because of the myriad of presentations and lack of clear definition, the severity of clinical presentation varies widely…”19

• “Cauda equina syndrome can be diagnostically challenging due to its wide array of symptoms and time to progress.”20

• “Delays in surgical intervention for CES may have many causes, most notably difficulties in diagnosis and referral compounded by the heterogeneity of clinical presentations.”21

These arguments go hand in hand with either subtle or overt patient blaming, focusing on the patient’s failure to present (or return) to the ED), and also lend themselves nicely (from the defense perspective) to supporting an Exercise of Judgment jury instruction.

Delays in surgical decompression may give rise to liability. The literature is replete with references to the need for decompression surgery within 48 hours. And defendants may cite this 48-hour period as a “window of safety”, within which urgent decompression may reasonably be delayed.

However, a comprehensive 2014 article stands in contrast to this proposition: “Currently, there is no strong evidence for safely delaying surgery up to any time point, although many authors refer to 48 hours since symptom onset as the recommended upper limit” and “[t]here is no strong basis to support 48 hours as a blanket safe time point to delay surgery.”22

A surgeon would certainly risk his patient’s well-being – and a malpractice claim – if she failed to perform decompression surgery as soon as reasonably possible in all but the most hopeless cases.

Causation

Because of the relatively unsettled nature of the current medical literature on CES, both claimants and defendants may find ammunition there. Two highlighted areas of conflict in this article include a claimant’s ability to prove causation at all with imperfect data, and how CES staging informs causation opinions.

A lack of supporting literature and underlying factual data means “you can’t say”

Claimants may continue to encounter defense experts who essentially argue “you can’t say” whether earlier intervention would have made a difference in the eventual outcome.

In the context of establishing a quantifiable difference in outcome due to an unreasonable delay in surgery, often there is also a lack of evidence of a patient’s signs and symptoms during the delay for a patient expert to rely upon for her or his opinion. It may be, for example, precisely because of the negligence of the defendant (in discharging the patient with pain meds and instructions to take it easy, who should be admitted for surgery) that no such data exists.23

And, while some current literature describes such deterioration as occurring in “unpredictable fashion”, making timing “challenging”24, a growing number of articles describe such deterioration as continuous and progressive, rather than stepwise in fashion: “A general consensus among spine surgeons is the acknowledgment that biological systems tend to deteriorate in a continuous rather than stepwise manner. It is probably more likely, therefore, that the earlier the intervention, the more beneficial the effects for the compressed nerves. This is probably especially so in acute CES.”25

This evolving consensus of a progressive deterioration allows for a plaintiff causation expert to extrapolate as to the likely outcome with earlier intervention from less than perfect data. And it accords with commonsense: surgical decompression prevents neurological deterioration.

CES staging and causation

The consensus view is patients who have not progressed to CES-R should be operated on urgently, as their chances for improvement are clearly improved with earlier surgical intervention.26 However, conflict still exists as to the urgency with which surgery should occur in patients who have already progressed to CES-R.

Defense experts may cite to literature that supports the idea that, once a patient has progressed to CES-R, there is no proof that urgent surgery produces better outcomes.27 And, there may be good reason to delay a surgery, such as if it is in the middle of the night, or there are issues with access to a surgical suite or team to safely perform the surgery.

On the other hand, literature supports that even CES-R patients may find symptomatic improvement in surgery. One such study noted that the bowel and bladder symptoms of CES-R patients improved 20%-90% with surgical intervention.28

Because there still exists such conflict, a stronger causation case can be made if a plaintiff expert can credibly argue the patient was CES-I at the time when surgery was indicated. Failing that, it may be difficult to support plaintiff’s burden on causation if the patient was already in retention (CES-R) at a time when she believes surgery should have occurred.

Conclusion

Cauda Equina Syndrome remains a relatively common source of litigation, due to both the often devastating nature of the injuries, and its often delayed diagnosis and treatment.

This article appeared in the May 2022 issue of WSAJ’s Trial News

- The authors thank WSAJ EAGLE David Kohles for his excellent work on this issue, including his article on CES published in Spine in 2004.

- Eren O. Kuris et al, Evaluation and Management of CES. The American Journal of Medicine (2021).

- If you would like more comprehensive and detailed information on these subjects, including copies of cited literature, please contact the author at tyler@cmglaw.com.

- American Association of Neurological Surgeons, Cauda Equina Syndrome, https://www.aans.org/en/Patients/Neurosurgical-Conditions-and-Treatments/Cauda-Equina-Syndrome, last accessed April 6, 2022 (hereinafter “AANS CES webpage”)

- N.V. Todd, An Algorithm for Suspected CES, Ann R Coll Surg Engl (2009); 91:351-60.

- AANS CES webpage. This is consistent with the authors’ review of potential cases involving allegations of delays and failures to diagnose CES. It is not uncommon for emergency department providers to chart “denies saddle anesthesia” as a pertinent negative when considering a diagnosis of CES.

- Anthony M. T. Chau et al., Timing of Surgical Intervention in Cauda Equina Syndrome: A Systemic Critical Review, World Neurosurg (2014) 81, 3/4:640-50.

- AANS CES webpage.

- Anthony M. T. Chau et al., supra.

- Brit Long, MD et al., Evaluation and Management of Cauda Equina Syndrome in the Emergency Department, Am J. Emerg Med 2020 Jan; 38(1): 13-18. Another recent publication omitted CES-C and defines CES using only three stages. See Eren O. Kuris et al., Evaluation and Management of CES, The American Journal of Medicine (2021).

- AANS CES webpage.

- John W Martel & J. Brooks Motley, Chapter 9: Atraumatic Acute Neck and Back Pain, in Neurologic Emergencies, American College of Emergency Physicians, Springer Publishing (Latha Ganti & Joshua N. Goldstein ed., 2018).

- A. Gitelman et al., CES: A Comprehensive Review, Am J Orthop. 2008;37(11):556-62.

- Such as, the physical exam did not in fact occur, or was cursory.

- N.V. Todd & R.A. Dickson, Standards of Care in CES, British Journal of Neurosurgery, (2016)30:5, 518-22.